-40%

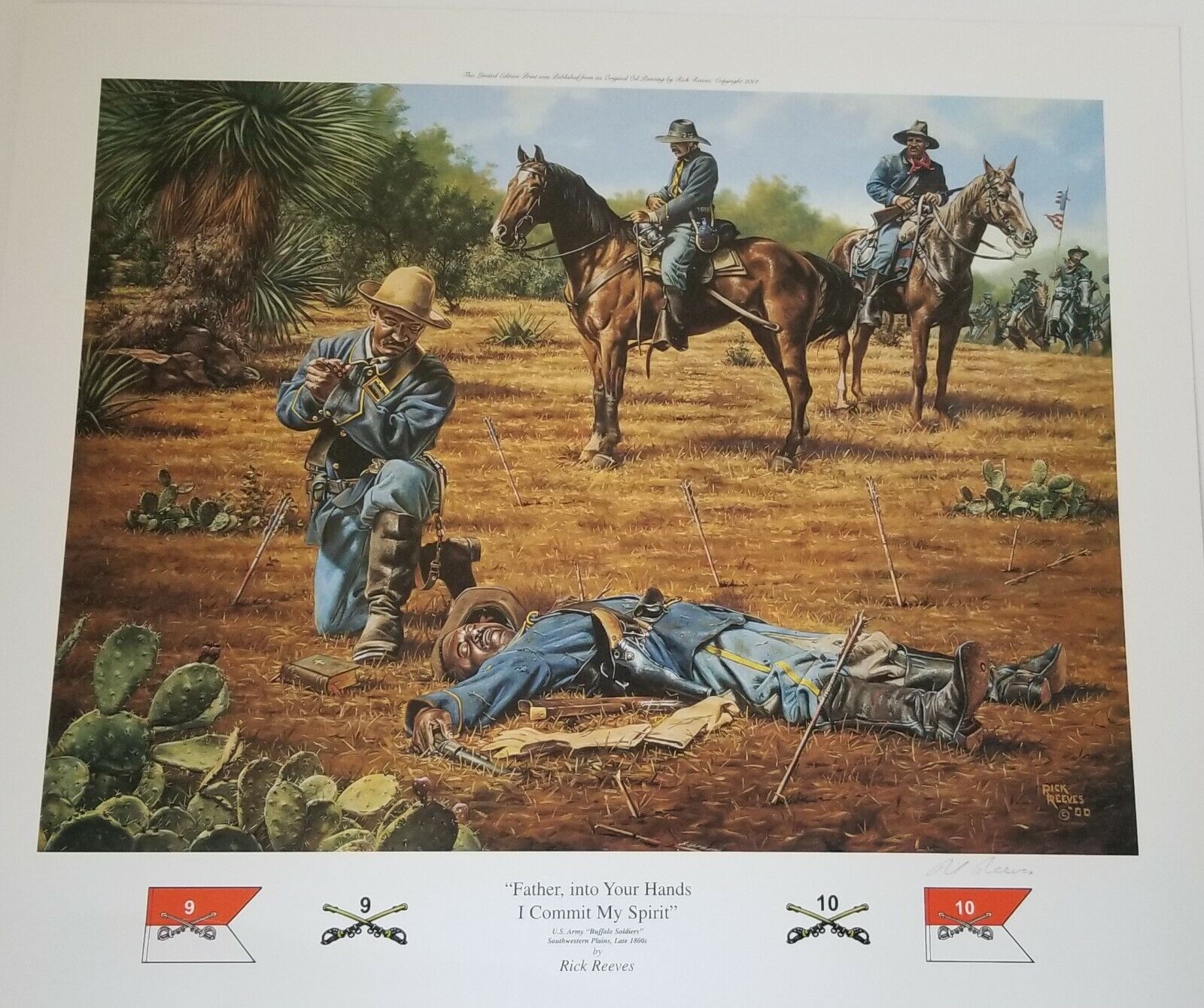

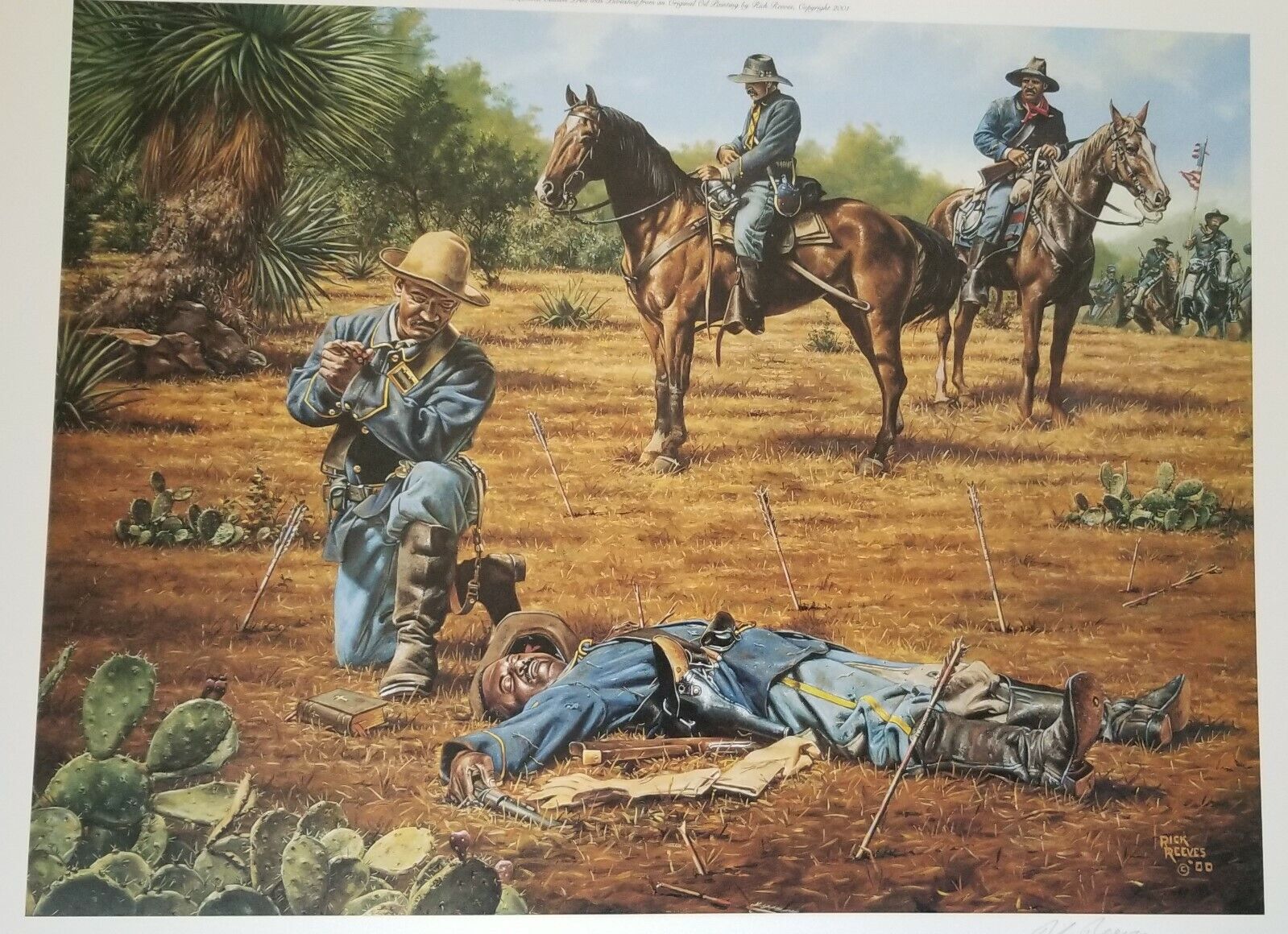

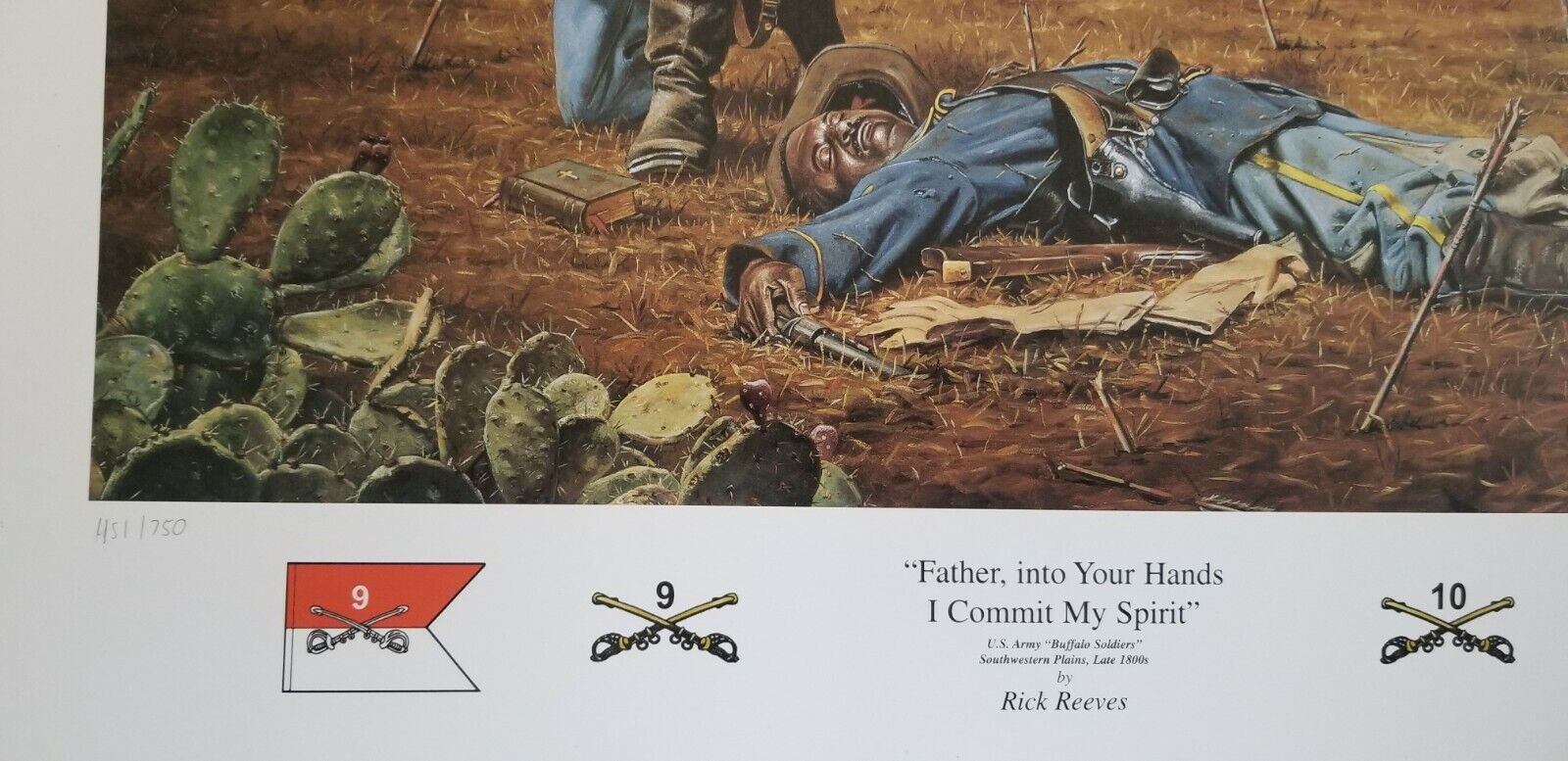

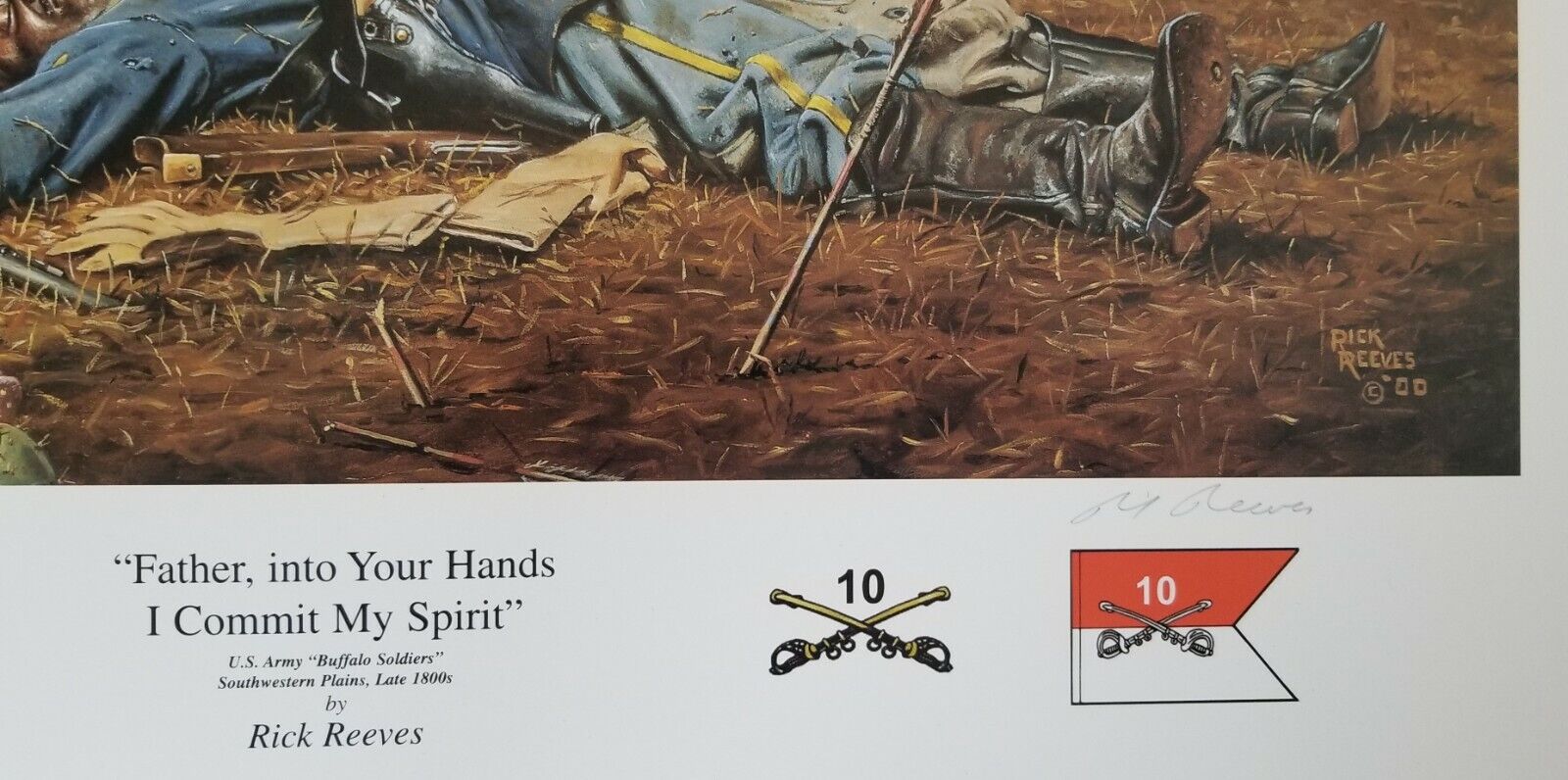

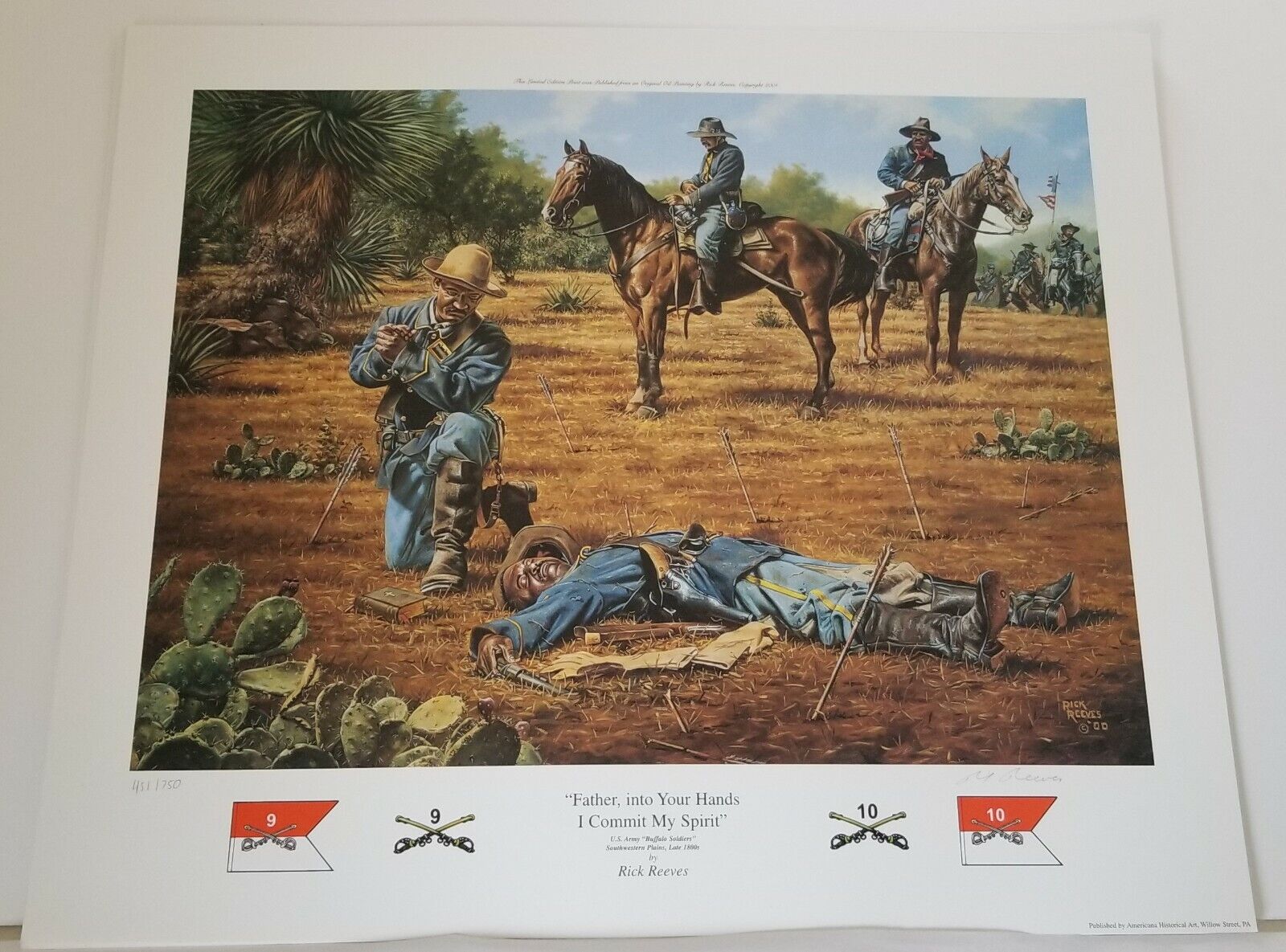

BUFFALO SOLDIERS - FATHER INTO YOUR HANDS by RICK REEVES limited edition art

$ 21.11

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

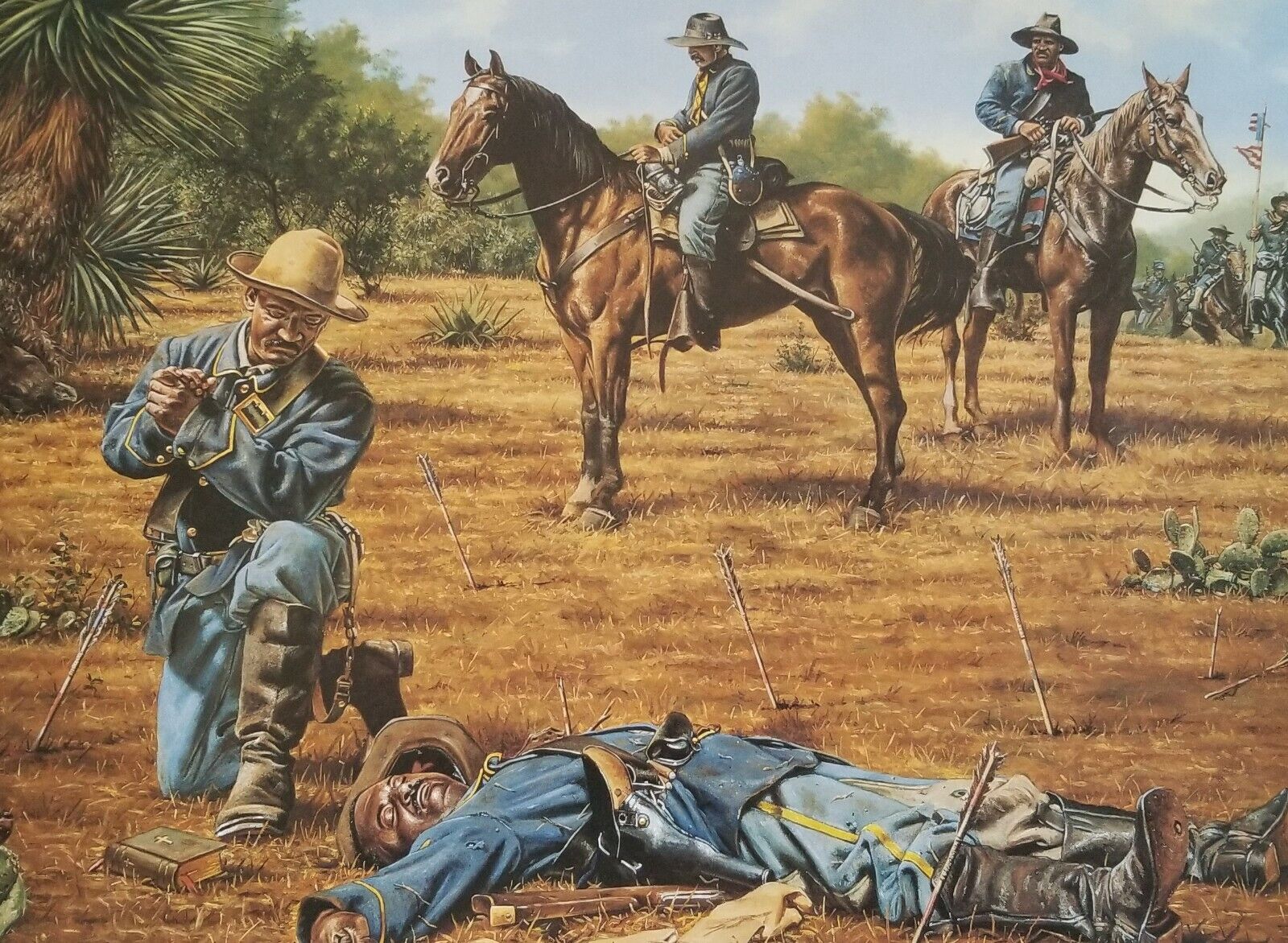

" FATHER INTO YOUR HANDS I COMMIT MY SPIRIT " - U. S. Army BUFFALO SOLDIERS Southwest Plains, late 1800's by Rick Reeves. Signed & numbered limited edition art print. SOLD OUT long ago. Measures 24" x 18" and in MINT condition. No Defects. Comes with Certificate of Authenticity. Published in 2000 and Limited to only 750 in the edition. Number will be different than the one pictured. Depicting a Buffalo Soldier saying a prayer over the body of a fallen comrade while two others keep watch. Insured USPS Priority mail delivery in the Continental US is $ 17.50. Will ship Worldwide and will combine shipping when practical.Will be shipped in a extra heavy duty tube that has to be purchased and not the cheap post office type that crushes easily. That is why the high (as some have complained) shipping cost.

Buffalo Soldiers

originally were members of the

10th Cavalry Regiment

of the

United States Army

, formed on September 21, 1866, at

Fort Leavenworth

,

Kansas

. This nickname was given to the Black Cavalry by

Native American

tribes who fought in the

Indian Wars

. The term eventually became synonymous with all of the

African-American

regiments formed in 1866:

9th Cavalry Regiment

10th Cavalry Regiment

24th Infantry Regiment

25th Infantry Regiment

Second 38th Infantry Regiment

Although several African-American regiments were raised during the

Civil War

as part of the

Union Army

(including the

54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry

and the many

United States Colored Troops

Regiments), the "Buffalo Soldiers" were established by

Congress

as the first peacetime all-black regiments in the regular U.S. Army.

[1]

On September 6, 2005,

Mark Matthews

, the oldest surviving Buffalo Soldier, died at the age of 111. He was buried at

Arlington National Cemetery

.

[2]

Sources disagree on how the nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" began. According to the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum, the name originated with the

Cheyenne

warriors in the winter of 1877, the actual Cheyenne translation being "Wild Buffalo". However, writer Walter Hill documented the account of

Colonel Benjamin Grierson

, who founded the 10th Cavalry regiment, recalling an 1871 campaign against

Comanches

. Hill attributed the origin of the name to the Comanche, due to Grierson's assertions. The Apache used the same term ("We called them 'buffalo soldiers,' because they had curly, kinky hair ... like bisons") a claim supported by other sources.

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

Another possible source could be from the

Plains Indians

who gave them that name because of the bison coats they wore in winter.

[7]

The term Buffalo Soldiers became a generic term for all black soldiers. It is now used for U.S. Army units that trace their direct lineage back to any of the African-American regiments formed in 1866.

Head of an American buffalo

Service

[

edit

]

During the Civil War, the U.S. government formed regiments known as the

United States Colored Troops

, composed of black soldiers and Native Americans. The USCT was disbanded in the fall of 1865. In 1867 the Regular Army was set at ten regiments of cavalry and 45 regiments of infantry. The Army was authorized to raise two regiments of black cavalry (the

9th

and

10th (Colored) Cavalry)

and four regiments of black infantry (the

38th

,

39th

,

40th

, and

41st (Colored) Infantry)

, who were mostly drawn from USCT veterans. The first draft of the bill that the House Committee on Military Affairs sent to the full chamber on March 7, 1866 did not include a provision for regiments of black cavalry, however, this provision was added by Senator

Benjamin Wade

prior to the bill's passing on July 28, 1866.

[8]

In 1869 the Regular Army was kept at ten regiments of cavalry but cut to 25 regiments of Infantry, reducing the black complement to two regiments (the

24th

and

25th (Colored) Infantry)

. The 38th and 41st were reorganized as the 25th, with headquarters in

Jackson Barracks

in

New Orleans, Louisiana

, in November 1869. The 39th and 40th were reorganized as the 24th, with headquarters at

Fort Clark

, Texas, in April 1869. The two black infantry regiments represented 10 percent of the size of all twenty-five infantry regiments. Similarly, the two black cavalry units represented 20 percent of the size of all ten cavalry regiments.

[8]

During the peacetime formation years (1865-1870), the black infantry and cavalry regiments were composed of black

enlisted soldiers

commanded by white commissioned officers and black noncommissioned officers. These included the first commander of the 10th Cavalry

Benjamin Grierson

, the first commander of the 9th Cavalry

Edward Hatch

,

Medal of Honor

recipient

Louis H. Carpenter

,

Nicholas M. Nolan

. The first black commissioned officer to lead the Buffalo Soldiers and the first black graduate of

West Point

, was

Henry O. Flipper

in 1877.

From 1870 to 1898 the total strength of the US Army totaled 25,000 service members with black soldiers maintaining their 10 percent representation.

[8]

History

[

edit

]

Indian Wars

[

edit

]

Main article:

Indian Wars

From 1866 to the early 1890s, these regiments served at a variety of posts in the

Southwestern United States

and the

Great Plains

regions. They participated in most of the military campaigns in these areas and earned a distinguished record. Thirteen enlisted men and six officers from these four regiments earned the

Medal of Honor

during the Indian Wars. In addition to the military campaigns, the Buffalo Soldiers served a variety of roles along the frontier, from building roads to escorting the

U.S. mail

. On April 17, 1875, regimental headquarters for the 10th Cavalry was transferred to

Fort Concho

, Texas. Companies actually arrived at Fort Concho in May 1873. The 9th Cavalry was headquartered at

Fort Union

from 1875 to 1881.

[9]

At various times from 1873 through 1885, Fort Concho housed 9th Cavalry companies A–F, K, and M, 10th Cavalry companies A, D–G, I, L, and M, 24th Infantry companies D–G, and K, and 25th Infantry companies G and K.

[10]

From 1880 to 1881, portions of all four of the Buffalo Soldier regiments were in New Mexico pursuing

Victorio

and

Nana

and their Apache warriors in

Victorio's War

.

[11]

The 9th Cavalry spent the winter of 1890 to 1891 guarding the

Pine Ridge Reservation

during the events of the

Ghost Dance War

and the

Wounded Knee Massacre

. Cavalry regiments were also used to remove

Sooners

from native lands in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Buffalo Soldier in the 9th Cavalry, 1890

Buffalo Soldiers

Buffalo Soldier troopers in formation, ready for inspection in Cuba.

United States Army

African Americans served in the U.S. Military during the Civil War and continued to serve afterwards. Many of these soldiers went on to fight in the Spanish-American War and the Philippine-American War. Although the pay was low, only a month, many African Americans enlisted because they could earn more and be treated with more dignity than they often received in civilian life.

In 1866, Congress established six all-black regiments (consolidated to four shortly after) to help rebuild the country after the Civil War and to fight on the Western frontier during the "Indian Wars." It was from one of these regiments, the 10th Cavalry, that the nickname Buffalo Soldier was born. American Plains Indians who fought against these soldiers referred to the black cavalry troops as "buffalo soldiers" because of their dark, curly hair, which resembled a buffalo's coat and because of their fierce nature of fighting. The nickname soon became synonymous with all African-American regiments formed in 1866.

In addition to their military duties, the Buffalo Soldiers also served as some of the first care takers of the national parks. Between 1891 and 1913, the U.S. Army served as the official administrator of Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. The soldiers were stationed at the Presidio of San Francisco during the winter months and then served in the Sierra during the summer months. While in the parks, soldier's duties included fighting wildfire, curbing poaching of the park's wildlife, ending illegal grazing of livestock on federal lands, and constructing roads, trail and other infrastructure. In 1903,

Captain Charles Young

led a company of Buffalo Soldiers in Sequoia and General Grant (now

Sequoia and King's Canyon

) National Parks. Young and his troops managed to complete more infrastructure improvements than those from the previous three years. They completed a road to the Giant Forest and a road to the base of Moro Rock. Their work on these new roads now allowed the public to access the mountain-top forest for the first time.

The Buffalo Soldier regiments went on to serve the U.S. Army with distinction and honor for nearly the next five decades. With the disbandment of the 27th Cavalry on December 12, 1951, the last of the storied Buffalo Soldiers regiments came to an end.

Buffalo soldiers were African American soldiers who mainly served on the Western frontier following the American Civil War. In 1866, six all-Black cavalry and infantry regiments were created after Congress passed the Army Organization Act. Their main tasks were to help control the Native Americans of the Plains, capture cattle rustlers and thieves and protect settlers, stagecoaches, wagon trains and railroad crews along the Western front.

Who Were the Buffalo Soldiers?

No one knows for certain why, but the soldiers of the all-Black 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments were dubbed “buffalo soldiers” by the Native Americans they encountered.

One theory claims the nickname arose because the soldiers’ dark, curly hair resembled the fur of a buffalo. Another assumption is the soldiers fought so valiantly and fiercely that the Indians revered them as they did the mighty buffalo.

Whatever the reason, the name stuck, and African American regiments formed in 1866, including the 24th and 25th Infantry (which were consolidated from four regiments) became known as buffalo soldiers.

The 9th Cavalry Regiment

The mustering of the 9th Cavalry took place in New Orleans, Louisiana, in August and September of 1866. The soldiers spent the winter organizing and training until they were ordered to San Antonio, Texas, in April 1867. There they were joined by most of their officers and their commanding officer, Colonel Edward Hatch.

Training the inexperienced and mostly uneducated soldiers of the 9th Calvary was a challenging task. But the regiment was willing, able and mostly ready to face anything when they were ordered to the unsettled landscape of West Texas.

The soldiers’ main mission was to secure the road from San Antonio to El Paso and restore and maintain order in areas disrupted by Native Americans, many of whom were frustrated with life on Indian reservations and broken promises by the federal government. The Black soldiers, facing their own forms of discrimination from the U.S. government, were tasked with removing another minority group in that government’s name.

The 10th Cavalry Regiment

The 10th Cavalry was based in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and commanded by Colonel Benjamin Grierson. Mustering was slow, partly because the colonel wanted more educated men in the regiment and partly because of a cholera outbreak in the summer of 1867.

In August 1867, the regiment was ordered to Fort Riley, Kansas, with the task of protecting the Pacific Railroad, which was under construction at the time.

Before they left Fort Leavenworth, some troops fought hundreds of Cheyenne in two separate battles near the Saline River. With the support of the 38th Infantry Regiment—which was later consolidated into the 24th Infantry Regiment—the 10th Cavalry pushed back the hostile Indians.

The cavalry lost just one man and several horses despite having inferior equipment and being greatly outnumbered. It was just one of many battles to come.

Indian Wars

Both the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments participated in dozens upon dozens of skirmishes and larger battles of the Indian Wars as America became obsessed with westward expansion.

For instance, the 9th Cavalry was critical to the success of a three-month, unremitting campaign known as the Red River War against the Kiowas, the Comanches, the Cheyenne and the Arapahoe. It was after this battle that the 10th Cavalry was sent to join them in Texas.

Troops H and I of the 10th Cavalry were part of a team that rescued wounded Lieutenant-Colonel George Alexander Forsyth and what remained of his group of scouts trapped on a sand bar and surrounded by Indians in the Arikaree River. A couple weeks later, the same troops engaged hundreds of Indians at Beaver Creek and fought so gallantly they were thanked in a field order by General Philip Sheridan.

By 1880, the 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments had minimized Indian resistance in Texas and the 9th Cavalry was ordered to Indian Territory in modern-day Oklahoma, ironically to prevent white settlers from illegally settling on Indian land. The 10th Cavalry continued to keep the Apache in check until the early 1890s when they relocated to Montana to round up the Cree.

About 20 percent of U.S. Cavalry troops that participated in the Indian Wars were buffalo soldiers, who participated in at least 177 conflicts.

Buffalo Soldiers Protect National Parks

Buffalo soldiers didn’t only battle unfriendly Indians. They also fought wildfires and poachers in Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks and supported the parks’ infrastructure.

According to the National Park Service, buffalo soldiers billeted at the Presidio army post in San Francisco during the winter and served as park rangers in the Sierra Nevada in the summer.

Buffalo Soldiers in Other Conflicts

In the late 1890s, with the “Indian problem” mostly settled, the 9th and 10th Calvary and the 24th and 25th Infantry headed to Florida at the start of the Spanish-American War.

Even facing blatant racism and enduring brutal weather conditions, buffalo soldiers earned a reputation for serving courageously. They fought heroically in the Battle of San Juan Hill, the Battle of El Caney and the Battle of Las Guasimas.

The 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments served in the Philippines in the early 1900s. Despite proving their military worth time and again, they continued to experience racial discrimination. During World War I, they were mostly relegated to defending the Mexican border.

Both regiments were integrated into the 2nd Cavalry Division in 1940. They trained for overseas deployment and combat during World War II. The 9th and 10th Cavalry Regiments were deactivated in May 1944.

Mark Matthews

In 1948, President Harry Truman issued Executive Order 9981 eliminating racial segregation in America’s armed forces. The last all-black units were disbanded during the 1950s.

Mark Matthews, the nation’s oldest living buffalo soldier, died in 2005 at age 111 in Washington, D.C.

Buffalo soldiers had the lowest military desertion and court-martial rates of their time. Many won the Congressional Medal of Honor, an award presented in recognition of combat valor that goes above and beyond the call of duty.

Buffalo Soldiers Legacy

Today, visitors can attend the Buffalo Soldiers National Museum in Houston, Texas, a museum dedicated to the history of their military service. Bob Marley and The Wailers immortalized the group in the reggae song “Buffalo Soldier,” which highlighted the irony of former slaves and their descendants “stolen from Africa” taking land from Native Americans for white settlers.